When I was at Nike, I was bemoaning the fact that somebody on my team wasn't performing -- and I was trying to get him to perform better. Finally, Phil Knight [Nike co-founder and chairman] said to me, "Mindy, what you really have to focus on is not trying to make ordinary people extraordinary. You need to hire extraordinary people." In today's world, talent is so critical to the success of what you're doing -- their core competencies and how well they fit into your office culture. The combination can be, well, extraordinary. But only if you bring in the right people.

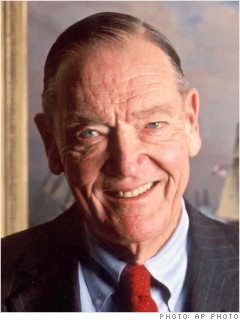

I was a runner for a little brokerage firm here in Philadelphia, delivering securities from one little brokerage firm to another. One of the other runners looked at me and he said, "Bogle, I'm gonna tell you everything you need to know about the investment business." And I said, "What's that, Ray?" And he said, "Nobody knows nuthin'." And it turns out, Ray was right. People say there are great performers out there, but it's a lot of randomness. None of us are smarter than the markets.

In my case it's not necessarily words of advice, but more advice I received through example. The example is Herb Kelleher [former CEO of Southwest Airlines], who I've gotten to know over the last 10 years. Knowing how great he's done, I've tried to hang out and watch and learn through osmosis. He is so good at listening, and has really taught me how important it is to listen to your employees. If you watch Herb in action, it really is phenomenal. He is completely engaged and never looks over your shoulders to see who else is in the room. It's not out of principle; it's just who he is.

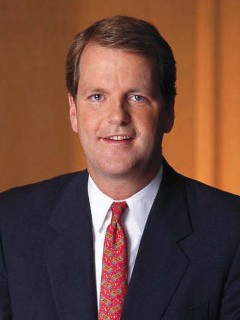

I try really hard now to have forums that allow employees to talk to me, rather than me being in front of 1,000 people. Four times a month, I put myself in a room with 30 or 40 pilots and flight attendants, and I talk for 10 minutes; they talk for 50. It's not just listening out of respect -- you can't imagine how much better you can do your job when you operate this way. When you're leading a big organization like an airline, there's a whole lot you can miss, so you have to start by listening to people. Then you can decide what the right course is.

I'm nowhere near where Herb is as a listener yet, but just yesterday, we had one of these meetings and someone told me about going to check in and all we had available was first class. She was traveling with her 10-year-old, and he wasn't allowed in first, so they couldn't fly. I don't think that's right. I didn't even know we had that policy, so it's going to change.

I graduated from Harvard Business School in 1984. Jobs were abundant, and I had many choices. I was torn between going to work at Goldman Sachs and a job at Mervyn's, which was one-third the salary. So I talked to my dad. He worked at General Mills. He said, "Of all the great leaders I've met, almost all started in that industry when they were young and learned every aspect of the business. Almost everyone started at the bottom."

The easy choice would have been to go to an investment bank. There was status and compensation and instant gratification. My dad said, "You can do that, but in a short period of time you're going to be wanting something else to do. If you're going to be significant at something, you've got to learn it from the ground up. There's no shortcut to success."

Retailing was fast moving, like playing a sport. I could have taken a job in strategic planning at Dayton Hudson [parent company of Mervyn's at the time], but I said, "No. I want to learn the business," and that's why I started in Glendale [as a store management trainee]. Today the same lessons apply to everything I've done, whether it's good design at Target or building the Apple Store. There are no shortcuts.

I remember when Apple went through a tough period. I didn't feel the pain as much as Steve [Jobs] did. When you are in the leadership position, the tough times can be much more difficult, because your job is really to shield your team through that, to keep them from taking shortcuts. We are building J.C. Penney for the next century. It's not about the quarter or the year.

Very early in my career, I had a tough boss. She had my best interests at heart, but she was a pretty critical person. She once pulled me aside and said, "Sometimes I feel like you just can't finish things. You start well, but you don't finish." Boy, I hated that that was her impression of me. My first instinct was, She's wrong -- I finish things. But the best advice is often the most painful advice, and you have to trust the person who's giving it to you. When you get criticism, ask yourself if it's relevant. In this instance the reason it hurt so much was that my boss was right. After our conversation, I took special classes to give me skills that I didn't quite have, so I couldn't use anything as an excuse to not finish a project. Now, in the back of my mind, I'm always asking, "Did I cross the finish line?"

www.fortune.com

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario