LIKE their comrades in Iraq and Syria, the jihadists of Islamic State (IS) in Libya were in retreat earlier this year. Their branch, considered the most lethal outside the Levant, was pushed out of Sirte, its coastal stronghold, in December and hit hard by American bombers in January. The blows seemed to dispel the idea that, as the core of its “caliphate” crumbled, Libya might serve as a fallback base for IS.

But although the jihadists are down in Libya, they are not out. And they may have international reach. Many of the fighters have regrouped in a swathe of desert valleys and rocky hills south-east of Tripoli. British police are probing links between Salman Abedi, the suicide-bomber who murdered 22 people at a concert in Manchester on May 22nd, and IS, which claimed responsibility for the attack. Mr Abedi was in Libya recently; his brother and father were arrested in Tripoli on May 24th. The militia holding them says the brother is a member of IS and was planning an attack on Tripoli.

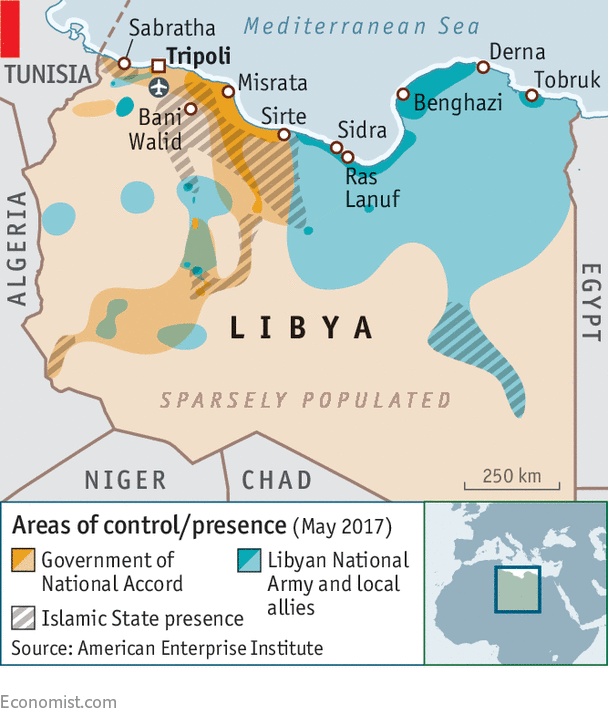

Chaos has been the norm in Libya since the uprising that toppled Muammar Qaddafi in 2011. Myriad armed groups, loosely aligned with rival governments in the east and west, vie for power. A UN-backed peace deal, signed by some of the adversaries in 2015, has failed to unite the country or create an effective state under the “government of national accord” (GNA). IS has fed on the chaos—and added to it, lately by attacking water pipelines and pumping stations.

There are thought to be around 500 IS fighters operating in Libya, not the thousands estimated before their recent setbacks. But there are perhaps 3,000 jihadists of all types. In a sign of how fluid things are, IS is now said to be receiving support from local al-Qaeda fighters, despite feuding between the groups’ leaders abroad. In Libya they operate in the same areas. Fighters move back and forth between them. “I can well imagine that they are co-operating on logistics and sharing information,” says Wolfgang Pusztai, a former Austrian defence attaché to Libya.

The terrain in the south makes it difficult to attack IS from the ground, say GNA officials, who oversaw the retaking of Sirte. But there are problems with air strikes too—the jihadists stopped travelling in large numbers after American bombers killed more than 80 of them in one set of strikes in January. Now they move in small groups along unpatrolled roads. The GNA says it is keeping tabs on them from a base near Bani Walid, while America is watching from the air. It has been flying surveillance drones over Libya from bases in Tunisia since last summer, and it is building a new drone base in Niger.

Neighbours worry that their own militants will find inspiration and training in Libya—and then return home. Chad closed its border with Libya in January, fearing an influx of jihadists. (It has since reopened one crossing.) Algeria has opened a new air base to guard its frontiers. Tunisia, which has suffered several attacks by jihadists, has built a 200km (125-mile) earth wall along its border with Libya. But even so, IS maintains cells near Sabratha, in the west, to help its fighters get in and out.

Europe, only some 400km away, is eyeing the situation with concern. The chaos has made Libya the main point of entry to Europe for African migrants. Despite more patrols, some 50,000 migrants are thought to have reached Italy by boat so far this year, over 40% more than in the same period last year. Some believe the smuggling business helps to finance terrorism—and that jihadists may be among those making the trip.

For now IS and its allies are keeping a low profile in Libya, if not elsewhere, as they try to rebuild their strength. Meanwhile, hopes of a settlement to the conflict look dim. The chaos is likely to continue, giving the jihadists an opportunity to reassert themselves at home.

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario