A car, a kitchen knife and an Islamist-inspired killer bring chaos to central London

“IT’S a simulation, no?” asked a confused tourist, as the emergency services hurried into action and a helicopter flew low overhead. This time, it was not. At 2.40pm on March 22nd—the anniversary of the terrorist assault on Brussels airport last year, which may or may not be a coincidence—a man using a car as a lethal weapon mowed down people on Westminster Bridge, crashed into gates outside Parliament and used a large kitchen knife to murder a policeman before being shot dead himself. It was precisely the kind of attack that Britain’s security authorities have been expecting. It was also the kind that is most difficult to prevent.

Two other people died and around 40 were injured, seven critically, including one woman who fell or jumped from the bridge into the River Thames. Among the injured was a party of French schoolchildren and three other police officers. As news of the attack spread, Parliament went into “lockdown” and the part of London that symbolises Britain’s democracy was sealed off.

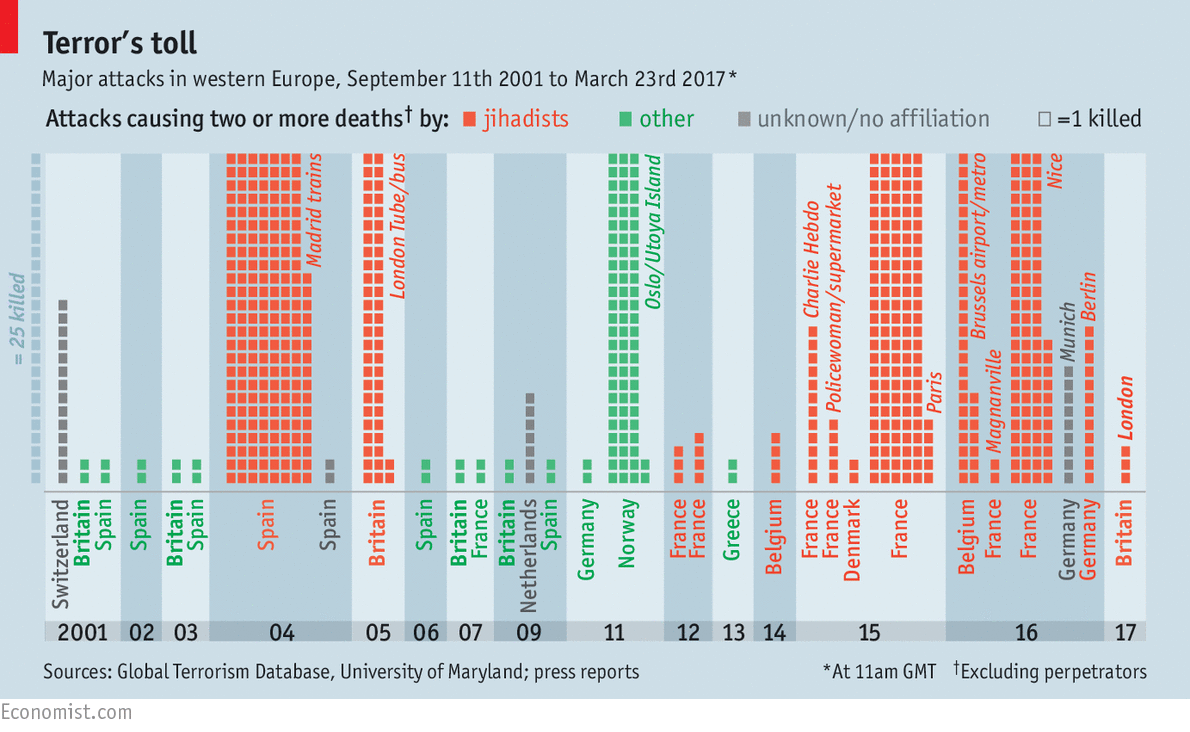

Later in the day Theresa May condemned the “sick and depraved terrorist attack”. The prime minister, who previously served as home secretary, declared: “We will all move forward together. Never giving in to terror. And never allowing the voices of hate and evil to drive us apart.” It was the deadliest terrorist attack London had suffered since the Tube and bus bombings of 2005 (see chart). But Parliament re-opened the following day.

As The Economist went to press, some details of the investigation into the attack had begun to emerge. Although it was a “lone wolf” assault of the sort seen several times during the past year in France and Germany, the British-born killer may have had helpers. On March 23rd police announced the arrest of eight people after a series of raids in London and Birmingham. What is not in doubt is that the perpetrator was inspired by Islamist extremism.

Although such an attack was anticipated—the first response was efficient and calm—the grim reality is that it may be the precursor to many similar ones.

Britain’s counter-terrorism police and intelligence agencies are among the best in the world and have a successful recent record. Since the murder of a soldier in east London in 2013, they claim to have thwarted 13 terrorist plots. At any time there may be up to 500 security-related investigations under way.

British security agencies have several advantages over their colleagues elsewhere in Europe. They are well funded, have state-of-the-art electronic surveillance capabilities and have largely banished the inter-agency rivalries that hamper counter-terrorist efforts elsewhere. Britain has some of the strictest firearms laws in the world and never joined the Schengen agreement, which allows border-free travel across much of the European Union. Its security services also have experience of fighting terrorism in Northern Ireland—as Britons were reminded this week by the death of Martin McGuinness, a proponent of terrorism and later peace in the province (see article).

But the problems they face now are different. Complex plots that involve detailed planning, numerous accomplices and the acquisition of guns or explosives offer plenty of opportunities for intelligence agencies to thwart them. But the kind of attack that Islamic State (IS) has become known for in the West is much cruder. Even if an individual is known to the authorities as an extremist who might one day pose a threat, he may slip off the radar. The Westminster Bridge attacker had been investigated “some years” ago by the intelligence services, Mrs May said.

And although IS may be on the point of losing its so-called caliphate in Iraq and Syria, its online propaganda remains as slick and seductive as ever. Radicalised, often disturbed young men are enticed into acts of violence against the societies in which they live. If anything, the threat posed by IS as it increasingly turns its attention towards the West is growing, possibly fuelled by the return of some battle-hardened jihadists to their homes in Europe.

Al-Qaeda, more active than ever in Yemen and under less pressure in Afghanistan, has learned from IS. Nonetheless, as the ban this week on taking electronic devices into the passenger cabins of aircraft flying from some Muslim countries suggests, the organisation has lost none of its fascination with aviation (see article).

After every terrorist outrage there is a temptation to look for the lessons that can be learned to make such an event less likely in the future. In the case of the Westminster Bridge attack, it is hard to see what those are. A car and a kitchen knife were all that was needed to bring terror to the capital for a few hours. But the security services in Britain are clear on one thing: policies that appear to demonise ordinary Muslims, as well as being wrong in themselves, are wholly counter-productive. The best technology in the world is no substitute for the human intelligence that comes from communities that do not feel alienated from the state.

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario