The European Commission’s huge penalty against Apple opens up a new front in the war on tax avoidance

The ruling is the most important—and controversial—moment so far in the war on corporate tax avoidance. Tax-justice campaigners hooted with delight. Apple was livid, and vowed to appeal. The Irish government may follow; its finance minister, Michael Noonan, would rather “defend the integrity of our tax system”, as he put it, than accept a windfall that would exceed Ireland’s annual health budget. Politicians in America, Apple’s home market, denounced the move as a “tax grab”.

The commission concluded that Irish rulings in 1991 and 2007 artificially lowered the tax Apple was due to pay, and that although the firm did not break any law, this arrangement was in breach of EU state-aid rules preventing member states from offering preferential treatment to particular firms. The spat centres on two Irish-registered subsidiaries that hold the right to use Apple’s intellectual property to make and sell its products outside the Americas. The commission argues that a dubious profit-allocation deal allowed most of their profits to be moved to a “head office” that existed only on paper and was tax-resident in no country—allowing Apple to shrink its tax rate in Europe to well below 1%.

The ruling is part of a broader assault on aggressive tax avoidance, led by Europe. This began several years ago, when post-crisis austerity produced calls for greater tax fairness. The commission is looking into questionable structures set up by several other (mostly American) firms, including Starbucks and McDonald’s—though these involve much smaller sums than Apple. The focus is on arrangements that allow the firms to minimise taxes paid in Europe on sales in the region, while simultaneously using deferral provisions in the American tax code to keep the profits offshore indefinitely—thereby also shielding them from a tax hit back home, where they would be taxed at a hefty 35% (minus any payments made in Europe) if repatriated.

European countries have been closely involved in efforts to create international consensus on how to close loopholes in cross-border taxation. These are led by the OECD, and are known as the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. The 44 participating countries (now 85) agreed on a set of reforms last year, but implementation is patchy. Some see the commission’s ruling on Apple as a sign that it has little faith in BEPS. The judgment certainly complicates international tax diplomacy.

America criticised the ruling, calling it “unfair”. It had warned that it might retaliate in some way if Brussels went ahead. It argues that the commission is trying to turn itself into a “supranational tax authority”, threatening the consensus achieved through BEPS on the crucial “arm’s-length principle” at the heart of transfer-pricing rules. These govern the prices that subsidiaries of a multinational in different countries charge each other for the products and services that flow between them.

The Americans are fretting mainly because the ruling signals that Europe will lay claim to some of the more than $2 trillion of profits that American firms have amassed offshore, under the deferral provisions. Policymakers in Washington believe only the federal government has the right to tax this, as and when it is brought home. The Brussels decision may spur American politicians to set aside their differences on tax reform and agree on a package with a reduced tax rate for profits that firms repatriate; better that than to let Europe dip into the offshore pot, they think.

Apple has come out fighting. It has denounced the ruling as unfairly retroactive, based on various “fundamental” misunderstandings of its operations and underpinned by iffy theories that have changed over time and that deviate from settled practice. It strikes “a devastating blow to the sovereignty of EU member states over their own tax matters and the principle of the certainty of law in Europe,” Tim Cook, its boss, harrumphed. The firm’s CFO, Luca Maestri, accused Ms Vestager’s team of “legal mumbo-jumbo” and poor maths: their calculation that Apple paid an Irish tax rate of under 1% for 2014 was arrived at using the “wrong denominator and the wrong numerator”, he claimed. Apple says it paid the equivalent of $400m in Irish tax that year at the statutory 12.5% rate.

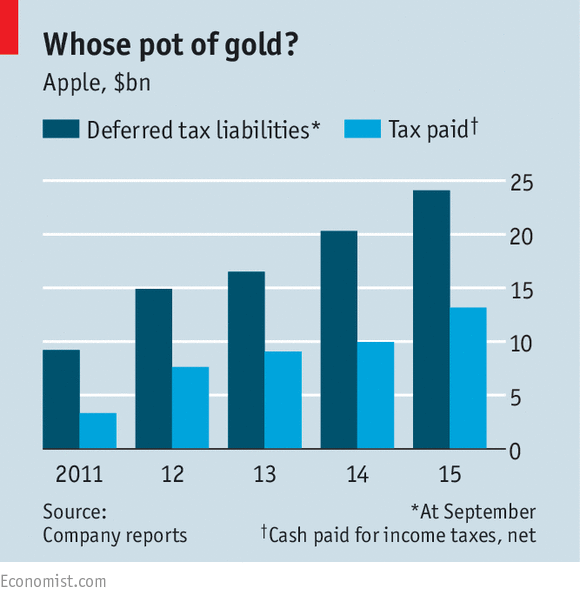

Apple also took issue with the assertion that the “head office” was stateless; the unit is, it says, taxable in America (in theory at least). It is also true that Apple pays substantial tax globally; last year it wrote cheques for more than $13 billion, which is comparable with the tax rate that many large American firms pay—though a sizeable chunk of what it owes is not paid straight away but is instead recorded as a deferred tax liability (see chart).

Ireland has its own reasons to chafe. It worries that being forced to collect would undermine its successful economic model: hosting multinationals that see Ireland as an attractive European base. “To do anything else [but appeal] would be like eating the seed potatoes,” said Mr Noonan.

In the commission’s view, Ireland is not the only country short-changed by Apple’s tax practices; others, in the EU and beyond, have lost out. They may now challenge its arrangements. Other firms have reason to worry, too. There is no reason to think Brussels’s probes will end with Apple and the handful of other companies already under public scrutiny. These cases will not be resolved quickly. Apple’s appeal could take a decade to grind through the courts. In the meantime, it will have to put the amount demanded in escrow. At 7% of its cash pile, that’s comfortably affordable. Not many companies could say that.

http://www.economist.com/

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario