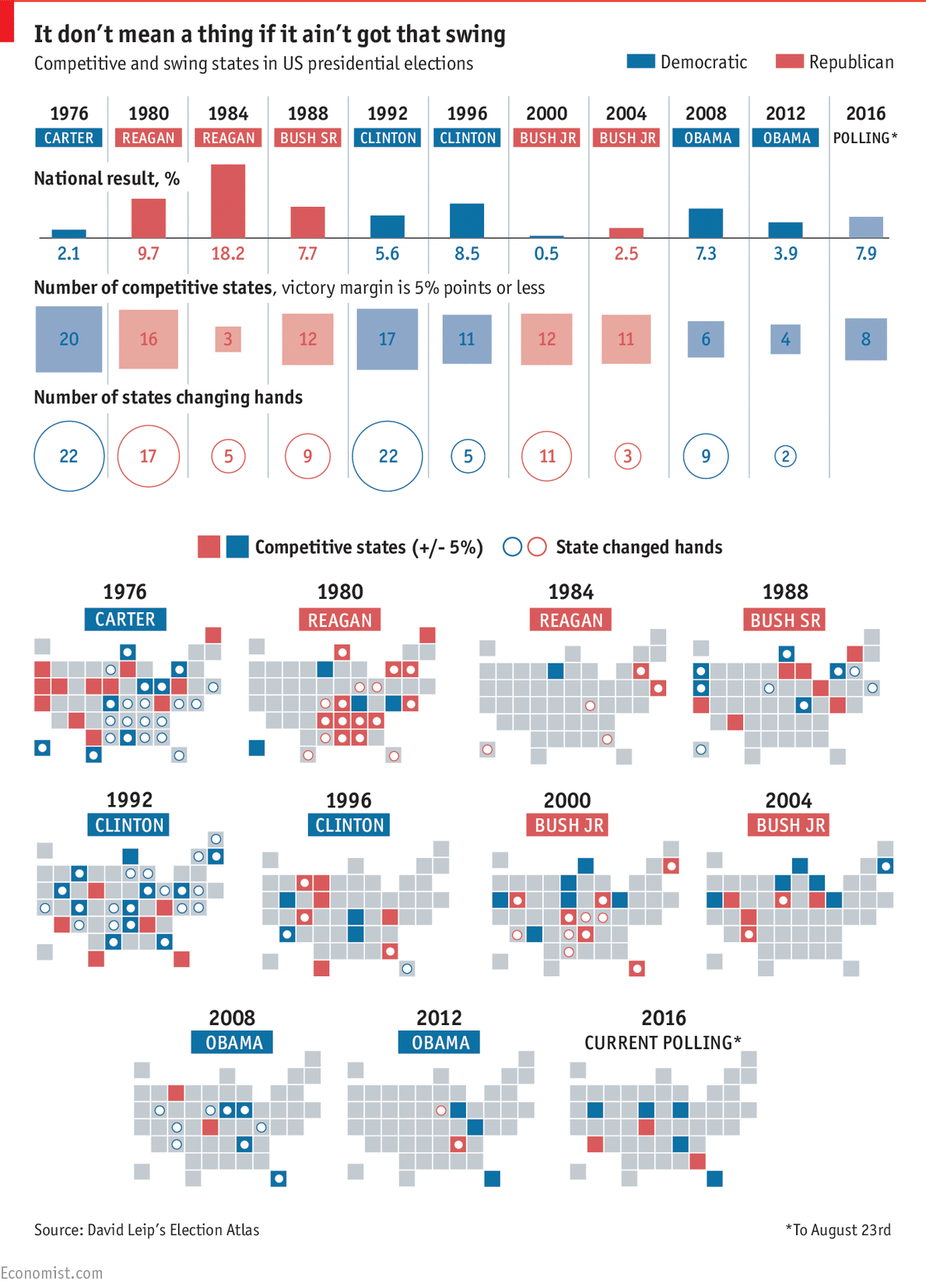

THERE was a time when American presidential candidates won real landslides. In 1964, 1972 and 1984 voters re-elected incumbents by margins of around 20 percentage points; all three of those victors (Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan) won over 90% of electoral college votes. More modest wins have also brought resounding mandates for new presidents, thanks to the winner-take-all arithmetic of the electoral college. Reagan won 91% of electoral votes in 1980 while “only” beating Jimmy Carter by ten percentage points. His successor, George H.W. Bush, secured 79% of the college in 1988 with just a 7.7-point victory over Michael Dukakis.

Such lopsided electoral-college margins now appear to be a thing of the past. Although Barack Obama beat John McCain in 2008 by 7.3 points, roughly the same margin as the elder Mr Bush achieved, he only secured 68% of electoral votes. The main reason is that the electoral college is less sensitive to changes in the popular vote than it once was. From 1948 to 1996, a gain of one extra percentage point in the popular vote corresponded to a pickup of four percentage points in the electoral college. Since 2000, that ratio has fallen to three.

For example, in the 1976 election, which Mr Carter won by two percentage points, 20 states were decided by a margin of five points or less. In contrast, George W. Bush won the 2004 vote by a similar amount, but the candidates were separated by fewer than five points in only 11 states. Similarly, half as many states were within a five-point margin for Mr Obama’s first victory than for George H.W. Bush’s.

Advertisement

|

According to Stacey Hunter Hecht and David Schultz, two political scientists who outlined the history of American “swing states” in a book published last year, one explanation for this trend is political and demographic “sorting” along geographic lines. In recent years liberals have tended to move to already liberal-leaning states. The same has gone for their conservative cousins. As a result, even presidential candidates who lose the national vote decisively can amass lopsided margins on their “home turf”. Mitt Romney, for example, won Wyoming by 41 points in 2012, even though Mr Obama beat him by four overall. These migration patterns have also increased the likelihood that states will vote for the same party from one election to the next, regardless of which side wins the presidency. That has made it harder for so-called bellwether states, with a long record of siding with the victor—as Maine did from 1832 to 1932, and Missouri from 1904 to 2004—to sustain this pattern.

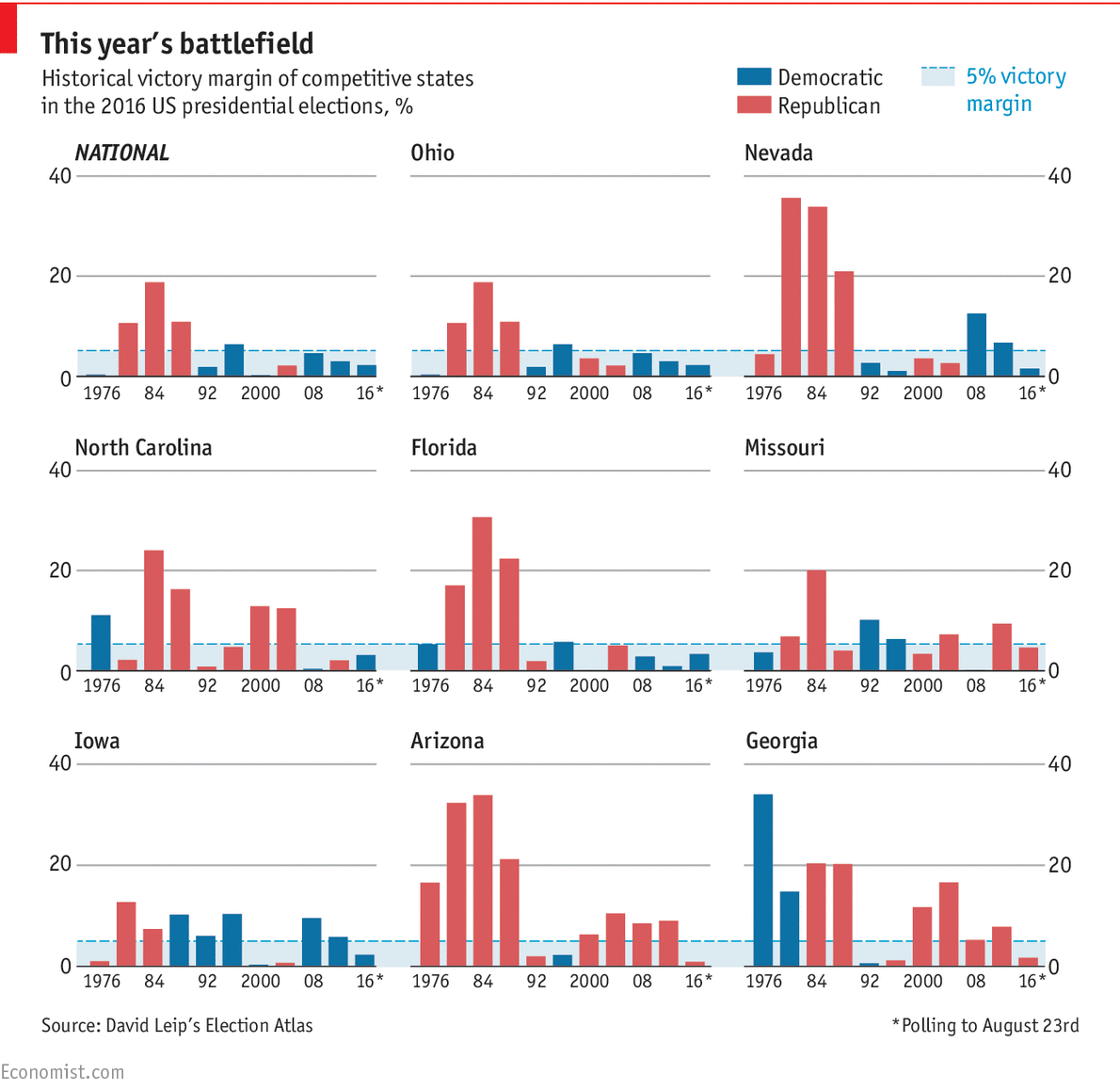

Nonetheless, even a highly sorted America is not immune to massive swings in the national mood. In 2008 Mr Obama won Indiana, a state that had not voted for a Democrat since 1964. This year polling indicates that two states previously seen as firmly in the Republican camp, Arizona and Georgia, now look competitive. South Carolina, an even more conservative stronghold, is not far behind. Donald Trump is prone to boasting of his ability to accomplish improbable feats. But turning the Deep South and Sun Belt blue is probably not what he has in mind.

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario