Cleverer use of data and investigative collaboration can help cut fraud

Cleverer use of data and investigative collaboration can help cut fraud

UNCLE SAM is being bilked, big-time. Losses from health-care scams alone are between $70 billion and $240 billion a year, reckons the FBI. An ever higher percentage of frauds (false claims for welfare payments, tax refunds and so on) are being perpetrated with stolen identities. Some 12.6m people—one every three seconds—fell victim to identity theft in the United States in 2012, according to Javelin Strategy and Research. The problem only grows as benefit programmes strive for efficiency and convenience, shifting applications online and making payments to prepaid debit cards, which can be bought in shops, require no bank account and allow money to be laundered quickly and easily. The self-proclaimed first lady of tax-refund fraud is Rashia Wilson (posing with the loot on her Facebook page, above) who, along with her eager associates, claimed bogus rebates of more than $11m.

A degree in computer science is not needed to steal personal data. Names, addresses and Social Security numbers can be nicked from doctor’s surgeries, nursing homes and hospitals, either by insiders (a medical assistant was indicted in June for allegedly selling hundreds of names to feed his crack habit) or outsiders (who may distract secretaries and grab patient logs). Swindlers commonly prise information from the unsuspecting over the phone by posing as, say, Medicare reps. Some use the identities of dead people after trawling genealogical or family-support websites. The Affordable Care Act is a gift: complaints about phone calls and visits from bogus Obamacare “navigators” are on the rise.

A favourite pursuit of identity thieves is tax-refund fraud, not least because the scope for abuse is so big: 145m individual income-tax returns are filed each year in America, of which three-quarters are entitled to a rebate. Using stolen personal details and made-up withholding forms, a fraudster can apply online for dozens of refunds a day, to be sent to addresses of his choosing. When the real taxpayer tries to file a return (assuming he’s alive), the IRS rejects it, and the mess can take months to sort out. So common is this scam that it has its own acronym, SIRF (for Stolen Identity Refund Fraud).

Some who have been caught at it admit to working on an industrial scale, putting in 12-hour days with a dozen or more accomplices, each filing return after return on laptops. Some street gangs are moving from drugs to refund fraud because it is more lucrative, less physically dangerous and, in some states, much less harshly punished. The craze has even spread to prisons. The IRS caught more than 170,000 dodgy requests from inmates between January and September of last year. How many slipped through the net is anyone’s guess.

The war against fraud is increasingly being waged from business parks in leafy suburbs such as Alpharetta, north of Atlanta. In an inconspicuous low-rise building belonging to LexisNexis, an online-information firm that is part of Reed Elsevier, dozens of computer racks, each holding 80 servers, link up with each other (and a sister site in Boca Raton) to form a vast supercomputer. These black boxes house a five-petabyte database, big enough to hold the DNA of America’s entire population 15 times over. To keep them from overheating, cold air is blasted against them through floor vents, then sucked into the ceiling to be re-cooled. In a nearby control room a team monitors the system on a giant screen filled with spider diagrams.

LexisNexis’s data trove includes everything from property, vehicle-registration and other public records to legal filings and proprietary data bought from firms that serve consumers, such as insurers. Along with other information providers, including credit bureaus such as Equifax and Experian, it has been busily developing its “risk solutions” business in recent years. A big part of this is helping the government spot fraudulent requests for cash, preferably before the money goes out of the door.

Some 30 state and federal agencies use fraud “filters” designed by LexisNexis that run requests against the millions of names, addresses and other bits of personal information in its database and flag those that look suspicious (because, say, they share an address with 20 similar requests). These can quickly identify patterns that would take months to spot through manual investigation. The filters are developed by “data scientists” who combine maths wizardry with data skills and knowledge of the government programme being defrauded.

Georgia is a pioneer. Its Department of Revenue uses LexisNexis to flash up potentially fraudulent requests. Those who make them are contacted and asked multiple-choice questions about past addresses, vehicles they have owned and the like. Only those who answer them all correctly get the refund. (They have two chances.) The results are impressive. Of the 4m returns filed in the state last year, 160,000 were found to be iffy. Total savings were $110m, of which Douglas MacGinnitie, the revenue commissioner, attributes $23m directly to the fraud filters, which cost just $3m to set up and run. Mr MacGinnitie embraced the analytics-based approach after experiencing refund fraud first-hand: his wife’s 2010 return was rejected because, it later transpired, someone had filed a fake return in her name, claimed the rebate on a prepaid card and vanished with the cash.

In another state (it won’t say which) LexisNexis helped uncover a group that had set up a “virtual apartment block” of post boxes in a shopping mall and used it to claim $16m of refunds for dead people from other states. The money, claimed in amounts below $10,000 so as not to trigger anti-money-laundering filters, disappeared to Russia. Numerous other fraudsters have had links to the former Soviet Union, including an Armenian-led group indicted in September that had used foreign students who were staying only briefly in America to claim $7m of bogus refunds using 2,000 stolen identities.

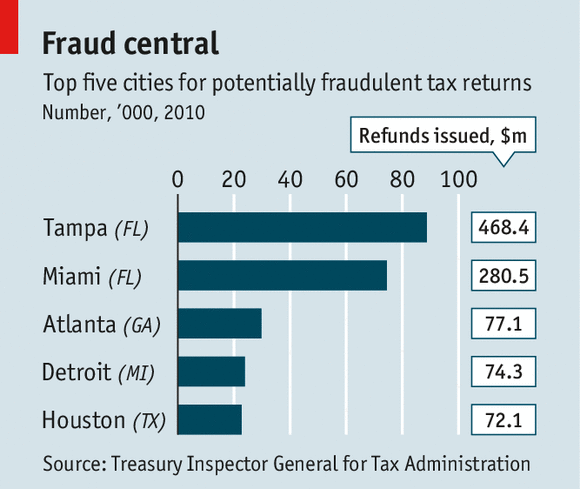

Florida has the highest rate of ID theft, and its joint capitals are Miami and Tampa (see table). Fake returns in and around Miami are more than 40 times the national average. A number of factors make the state vulnerable to such scams, among them its crowds of pensioners, large numbers of immigrants with poor English (who can be more easily duped into disclosing personal information) and its high rate of people who do not have to file tax returns (meaning more stolen numbers can be used without detection, because they do not generate duplicate filings). So many people stopped by Tampa police in 2011 were found to have lists of stolen IDs on them that the city’s exasperated mayor, Bob Buckhorn, declared the IRS “missing in action”.

The agency responded last year by creating a task-force, the Tampa Bay ID Theft Alliance, with federal prosecutors, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, Tampa’s police, county sheriffs and Crime Stoppers. This has helped in a number of ways. Leads are more easily shared. IRS investigators benefit from a closer relationship with local law-enforcers who are nearer the action. As one task-force member puts it: “This type of fraud is white-collar but also street-level, so it makes sense to pool resources.”

As a combined force, the group has been more effective at lobbying for change. It persuaded state lawmakers to make it a felony to be in possession of more than five Social Security numbers without a good excuse. (Previously, even someone with 500 could walk free unless prosecutors could prove intent to defraud, which is tricky.) It has also convinced local banks and credit unions to call when they see unusual withdrawals from ATMs, rather than merely filing suspicious-activity reports. These measures have helped push up convictions and may have spurred the increase in sentences, too—including the 21-year jail term handed in July to Ms Wilson.

The cost of not checking

Such initiatives are helping to soften criticism of the IRS, which peaked after a report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration found the agency might have sent out 1.5m potentially fraudulent refunds in 2011, including 655 to a single address in Lithuania. (In 2010, almost 4,900 went to the five most popular American addresses.) The IRS insists it is getting to grips with the problem. It has doubled the number of employees working full-time on ID theft to 3,000, even as its budget has been cut. This has helped reduce the average time it takes to resolve cases from ten months to four, and has raised the amount of fake refunds that are blocked before being sent out to $20 billion in the 2012 tax cycle, from $14 billion the year before. The IRS could cut losses further if it were able to delay posting refund cheques until it had time to cross-check them against income data from employers, which it receives weeks later. But that would require an act of Congress, and there is little political support for making people wait longer for their money.

Like the IRS, the Centres for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which administers those two programmes, is increasingly using “big data” to screen demands for money. Florida’s department of children and families, which doles out Medicaid payments, food stamps and cash assistance, recently extended a four-county pilot project with LexisNexis across the state after it flagged up dodgy online applications at an annualised rate of $60m—more than 50 times the project cost. The filters caught one woman who was claiming food stamps in all 50 states.

Officials in New York City are also using computing power to cut fraud losses, egged on by its outgoing mayor and data evangelist, Michael Bloomberg. Its social-services department is developing an algorithm that will identify those recipients most likely to have unreported income. The key, says James Sheehan, chief integrity officer of the city’s Human Resources Administration, is to combine such analytics with traditional detective work, such as property visits and phone calls.

It may seem odd that more agencies have not adopted this approach, given its apparently healthy return on investment. Some have just been slow to twig or have got caught up in other priorities, not least the Obamacare roll-out. Others have shown interest, but have been unable to secure funding or to get other agencies to work with them. States are also being held back by federal caution over the new data-driven approach. Take food stamps. The Department of Agriculture (USDA), which oversees the scheme, requires manual, paper-based verification of applicants, based solely on the information they provide. Florida was the first state to receive a waiver allowing it to verify electronically, using data from third parties. The USDA wants to see its system in action for several quarters before it grants the exemption to others.

States that lag behind may see things get worse before they get better. The Tampa task-force believes that several tax-refund fraud rings may have left Florida to set up operations in other states, including Texas and Missouri. Mr MacGinnitie says attempted tax fraud seems to be down this year in Georgia, but it is too early to say if that is because the swindlers have gone elsewhere, or because they have got more astute. They tweak their techniques as required. Some have moved from filing with stolen Social Security numbers to using Individual Taxpayer Identification numbers, which are handed out to legal immigrants. Others have found that filing joint returns helps them slip through the net. As one of the task-force members concludes: “We evolve, they evolve.”

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario